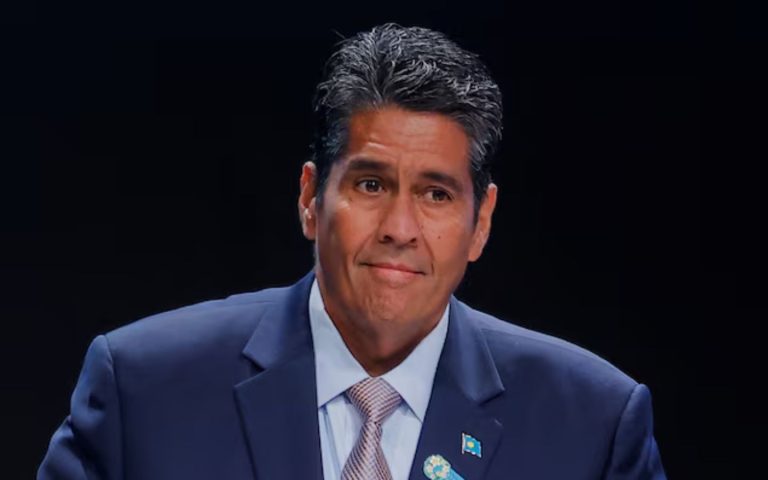

Photo courtesy of Island Institute. Retrieved from downeast.com

Excerpt from downeast.com

The introduction of the Island Institute Fellows program, in 1999, helped cement the organization’s reputation. “We didn’t invent this model,” Conkling notes, “but we knew what kind of fellow would work in which community, and we were good at matching them, and we were good at identifying future leaders.” Soon, communities up and down the coast were reaching out to the Island Institute to request fellows of their own for help with local projects. “There’s a wicked-tight network out there, and the coconut wireless is pretty effective,” Ralston adds. “People started coming to us for all sorts of things.” Recently, the old pals and colleagues met up at Ralston’s photography gallery, in Rockport, to reflect more on the long run of the fellowship program.

Where did the idea for the fellowships first come from?

Conkling: The backstory is that in the 1990s there was a lot of cognitive dissonance about what was happening to the lobster fishery in Penobscot Bay. The federal scientists who make the regulations were saying the fishery was on the verge of collapse and the industry needed to be cut back by 50 percent, but fishermen were saying the population was booming. The government was basing their decision off landings data, but some other crucial population statistics were missing. So, in 1998, we got a big federal grant to study lobster dynamics in Penobscot Bay. The only way to collect that missing data was to station graduate students on lobsterboats, which required the trust and participation of fishermen, which is what we brought to the table. We thought if we got a dozen boats to participate in this sea-sampling project, that would be a win. But that first summer, we got on 78 lobsterboats, which was a complete revelation. The insight on a larger scale was that the grad students were young, they didn’t pretend like they knew everything, and they were meeting the lobstermen on their home territory.