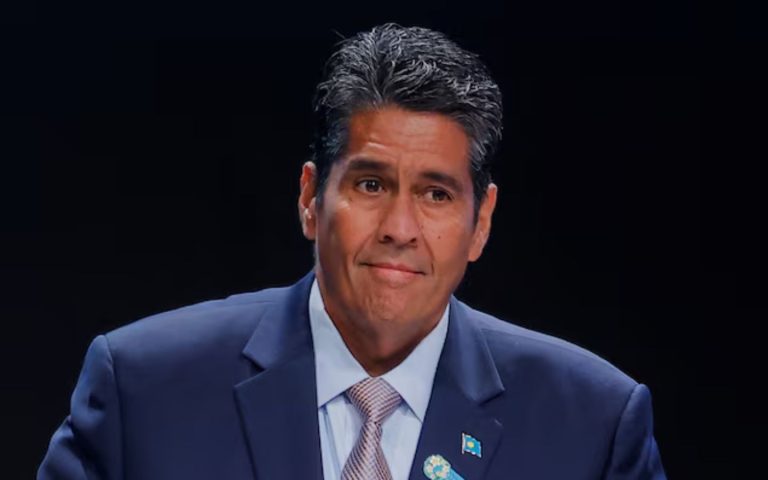

Photo courtesy: © CONAF-FAO / Pilar Cárcamo. Retrieved from fao.org

Excerpt from fao.org

On a remote Chilean island at the centre of Lake Ranco south of the Andes, native trees are making a comeback thanks to the restoration efforts of Indigenous Peoples, like Anita Neguimán Antillanca.

Like other Mapuche Huilliche Indigenous Peoples on Huapi Island, she’s been planting fruit-bearing Chilean hazel (Gevuina hazelnut) and other native trees to preserve her way of life – and the traditional knowledge of her people, which has been passed down from generation to generation.

Unsustainable land use practices had transformed the island’s landscape from a forest filled with oak (Nothofagus obliqua), raulí (Nothofagus alpina), coihue (Nothofagus dombeyi) and laurel (Laurelia sempervirens) trees to isolated clusters in remote areas.

As the native forest became more fragmented, replaced by exotic species such as eucalyptus, the soils became poorer and drier, and the island and its population became more vulnerable to the effects of climate change. Changes in the forest also reduced the availability of water for drinking and irrigation.